History of flight begins with an idea

History of flight begins with the ancient Chinese invention of kites long before the launch of rockets in the twelfth century. The idea of people flying was present in both legend and folklore through some sort of magical properties. In the Middle Ages, the emulation of birds flapping their wings was another idea that persevered for many hundreds of years.

Leonardo da Vinci studied this concept. He eventually concluded that man’s muscular system was not sufficient to perform the wing flapping function. He applied his anatomical and engineering knowledge to designs and drawings. These designs and drawings in other areas of flying mechanisms were far ahead of his time.

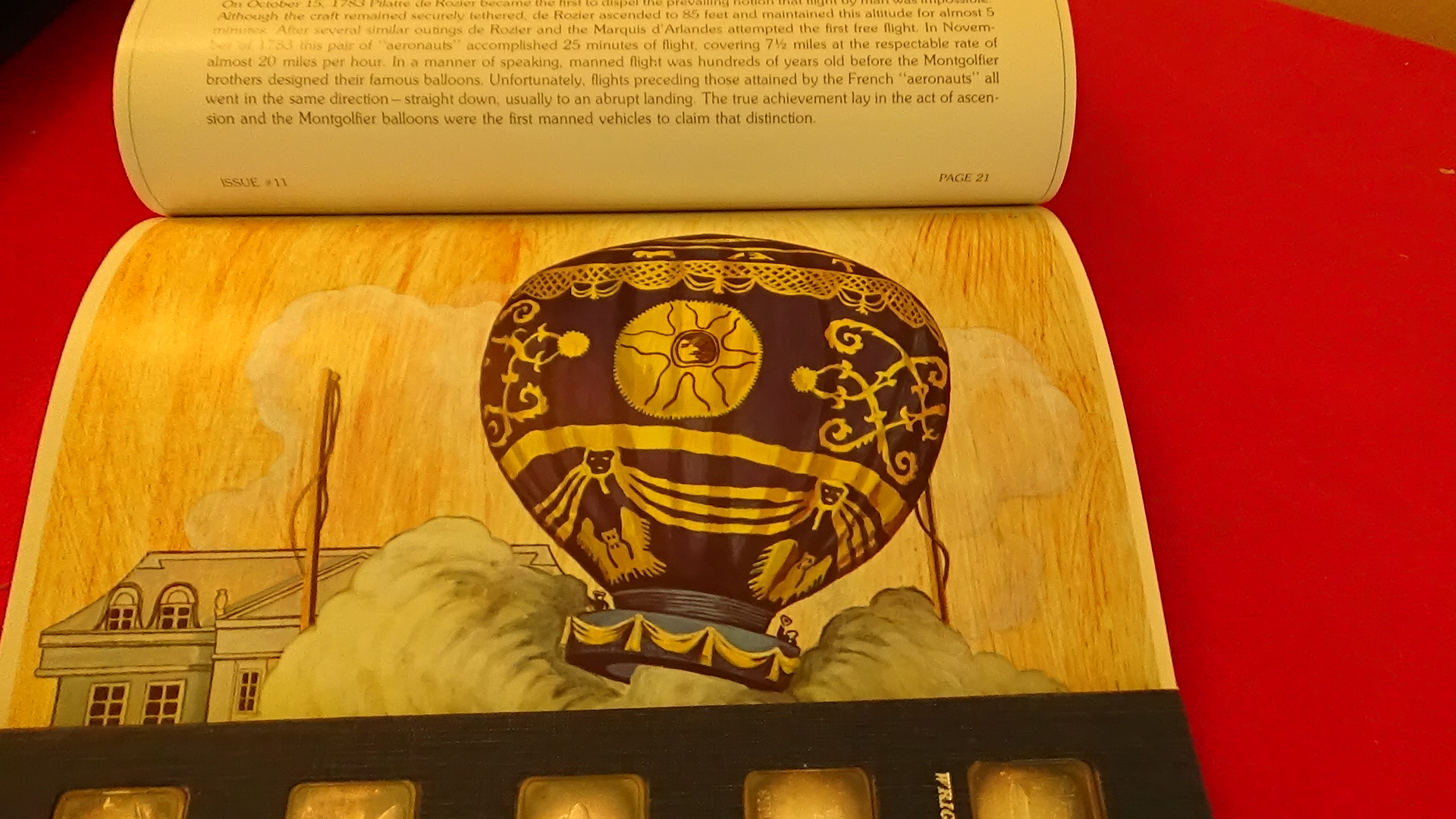

The history of flight journey continued in the eighteenth century. A hot air balloon built by the Montgolfier brothers carried the first man in the air in 1783. This ushered in the age of winged flight using balloons and powered airships. Names such as Blanchard, Green, Wise, Giffard, Lebaudy and Santos-Dumont all contributed to the history of flight.

The basics of modern aerodynamic structure were forged in the nineteenth century. Ader, Cayley, Pilcher and Chanute developed theories, principles and laws of aircraft design and construction. The Wrights, Curtiss, Farman, Voisin and others developed planes based upon the work and dreams of the earlier history of flight pioneers.

History of flight before the modern airplane

Joseph Montgolfier was a paper maker by trade. He was inspired to use hot air as a means of lifting objects into the air while watching sparks and ashes rising upwards in his heated fireplace. He and his brother, Etienne, experimented with finely-woven bags filled with warm air. The brothers called these bags “aerostatic machines”. These increasingly spherical bags evolved into the present form of a balloon.

In September of 1783, the Montgolfier balloon made its public debut at Versailles, before King Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, his court and 130,000 onlookers. The balloon was equipped with a cage containing a sheep, a duck and a rooster. This use of animals as experimental subjects set an aerial precedent still respected by modern pioneers of space exploration. The success of this flight and the survival of its barnyard passengers eventually led to manned flight.

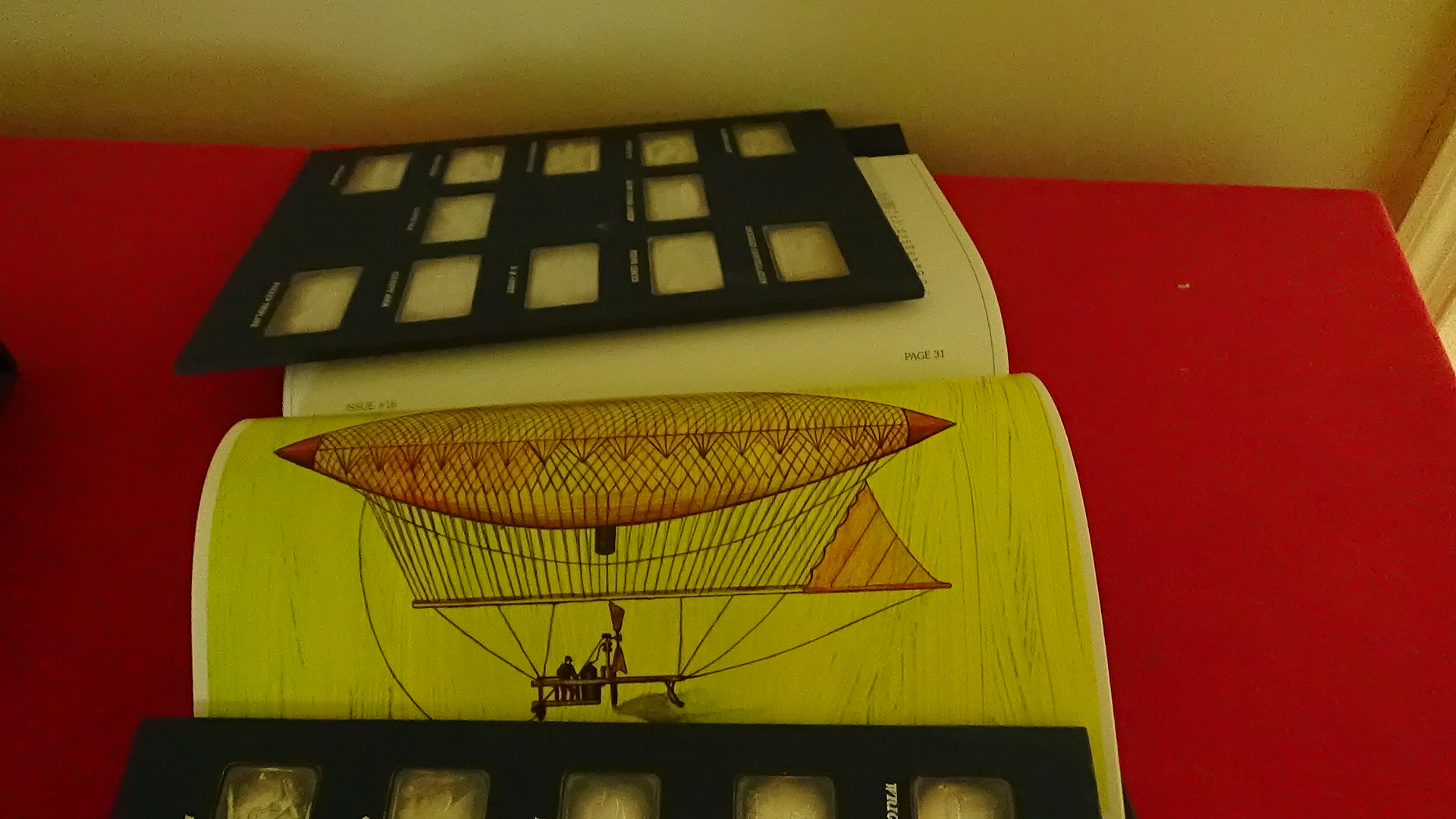

A French balloonist, Henry Giffard, developed a practical means of controlling flight. His idea was to use a steam engine to turn a large air screw. The Giffard Airship was tapered at both ends and had the appearance of a huge cigar. The inaugural flight, in September of 1852, proved that man could not only scale the clouds, but could navigate against the strong forces of wind. His airship pioneered the use of the air screw and became the first steerable lighter-than-air craft. Henry Giffard’s additions to navigational technology laid the ground work for the inventions of the famous dirigible magnate, Count Zeppelin, over fifty years later.

The work of Clement Ader in the field of powered flight ranks him highly in the history of flight and aviation. Ader conceived the design for the monoplane form with swept-back wings. His conception of the enclosed cockpit, the use of twin screws and a wheeled undercarriage are still integral components of many modern aircraft. Pioneers of powered flight and several of his pupils including the Voisin Brothers acknowledged his superiority in the field of aviation engineering.

In October of 1890, thirteen years before the Wright Brothers achieved their success at Kitty Hawk, Clement Ader “flew” an aeroplane. The bat-shaped device, powered by a lightweight Ader steam engine, may be the true claimant to the title of “the first successful aerodyne.” Ten spectators witnessed the rise of his “Eole” to eight inches off the ground. This historic “flight” covered an estimated 160 feet.

However, in spite of the fact that Ader actually did ascend, the controversy is over whether or not the small distance qualifies for consideration as true flight in the history of flight. However, this skyward excursion did provide a giant leap for aviation. Ader continued his work and produced a series of craft known as Avion. The planes were unsuccessful. However, their title came into common usage as the French term for aircraft.

History of flight and the launch of powered flight

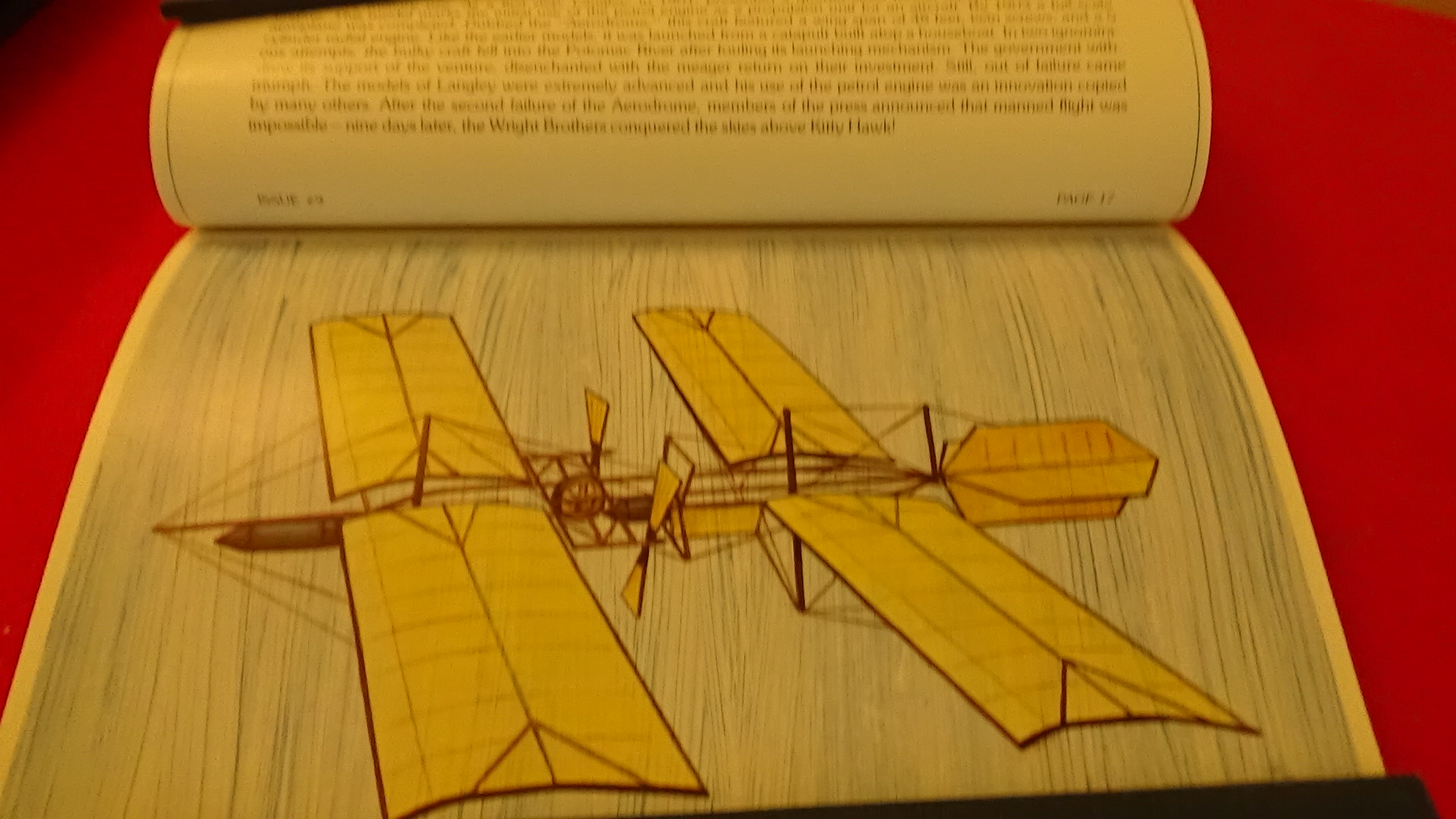

The achievements of Samuel Pierpont Langley paved the way for the Wright Brothers’ successful experiments in powered flight. By the 1880’s he was employed as the Director of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC. During his tenure in this position, he developed an avid interest in the “art of flight.” In 1891, after studying the anatomy of birds, he built a series of steam-powered model airplanes. The first four of these were inadequate for flight. By 1896, his fifth and sixth models were soaring off under their own power.

News of his efforts had been relayed to President McKinley, who offered financial assistance to the museum director. The conditions of this subsidy required Langley to develop a full-sized aeroplane suitable for military use. As a first step, Langley, in 1901, presented a quarter-sized model equipped with a petrol engine. This model marks the initial use of the petrol engine as a propulsion unit for an aircraft. By 1903 a full-scale aeorplane was completed. Dubbed the “Aerodrome,” this craft featured a wing span of 48 feet, twin screws and a 5-cylinder radial engine.

Orville and Wilbur Wright made four man carrying controlled powered flights at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17, 1903. Orville Wright piloted the first flight. He flew a distance of 120 feet in 12 seconds. The remaining flights were of greater distances and duration.

Both brothers were bicycle makers from Dayton, Ohio. They both possessed thorough mechanical and scientific knowledge. They studied the attempts and writings of previous designers – Lilienthal, Pilcher and Chanute. They corresponded primarily with Octave Chanute and kept a journal of their progress. They began their design with tethered gliders or kites in 1900. They moved on to manned gliders in 1902. After making many controlled gliding flights, they were ready for powered flight.

To their credit their design and construction of a four-cylinder gas engine, powering two chain driven propellers proved to be successful in the history of flight. The Wright brothers utilized the most applicable factors in the right direction launching the era of controlled powered flight. Their concept of wing warping for lateral control was worked out from earlier trials with gliders. The brothers had this method of control patented.

The design features of the Wright Flyer I evolved over years of research and experiments using a wind tunnel of their own design. The Flyer I had a wingspan of 40 feet, gross weight of 750 pounds and a 12 hp gas engine. They developed more Flyers. The brothers operated without much publicity. The press, public and government were all skeptical of the Wright’s accomplishments.

It wasn’t until 1908 that the Wright brother finally impressed the aviation world with the Wright Flyer III. In the same year, Orville impressed the United States government with the military potential of the airplane. At the trials at Fort Myer, Virginia the Wrights were awarded one of the first government contracts for an aircraft. In the meantime, Wilbur had returned to France to promote the Wright Flyer. He succeeded in convincing the Europeans of the superiority of the Wright airplane. The Wright brothers had finally received their well-earned recognition.

History of flight in the early twentieth century

The United States Post Office Department began the first official regularly scheduled air mail service on May 15, 1918 between the cities of Washington, Philadelphia and New York. In spite of the initial problems of organization during wartime limitations, the project soon proved its feasibility because of the dedicated efforts of everyone involved in the venture. Within three months, civilian pilots were hired. The United States Air Mail Service was on its own as a distinct branch of the U.S. Post Office Department.

Mail had been carried by air under various conditions, contracts and individual efforts since the days of balloons. The United States Post Office Department established the first true air mail service in the world. Though a civilian operated agency, the aircraft used were all military types. Charles A Lindbergh flew and bailed out in a parachute a few times on the Chicago to St. Louis route. The legendary Jack Knight flew a DH-4 from North Platte to Omaha, Nebraska. The next part of the route was to Chicago for a total distance of over 700 miles on February 22, 1921. This heroic ten-hour flight through most adverse conditions earned Jack Knight a place in the Air Mail Hall of Fame.

The most famous moment in the history of flight occurred on May 21, 1927. Charles A Lindbergh successfully crossed the Atlantic Ocean on this day arriving in Paris, France. A New York hotel magnate offered the 25-year-old aviator a prize of $25,000 for the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris. The former barnstormer and airmail pilot flew a plane called the “Spirit of St. Louis."

Spirit of St. Louis

Spirit of St. LouisBattling adverse weather conditions and frigid temperatures, the “Spirit of St. Louis” plodded along its 3,610- mile journey at an average speed of 107 miles per hour. After 331/2 hours of solitary confinement, Lindbergh landed in Paris. This concluded the fifth non-stop crossing of the Atlantic. Huge Parisian crowds congratulated the American. Lindbergh became the subject of unprecedented public adulation in the United States. His accomplishment made him the most beloved hero of a generation of Americans.

The history of flight continues at the Smithsonian National Air and Space museum.